Learning from Brasília

The question of the monument has always been topical in debates on architecture. Monuments speak to our imagination, and we are keen to select them as highlights of our architectural past. Even though we have lost our faith in strict guidelines for monumental representation some two centuries ago1, we have not yet fully disbanded the appeal of the monument. Representation, however, is no longer easily acquainted with the ideals and stern forms so long sought after by nineteenth century intellectuals2. Meaning has dislodged from the architectural object. With his classification of monuments into intentional and unintentional, Alois Riegl already pinpointed this far-fetching characteristic of symbolic meaning: it is implied on something, instead of belonging to it. The meaning of a monument can change, and as soon as the symbolic power of the expression loses strength, this process becomes more agile and transient.

For architecture to become monumental, many a claim is directed to manifestations of size or esthetic categories such as the sublime. In the third chapter of his "Lamps on Architecture", called "Lamp on Power", John Ruskin wrote that "every increase in magnitude will bestow upon it a certain degree of nobleness", while William Holford nearly a century later affirmed that "in both its favourable and its unfavourable senses the word "monumental" suggests magnitude and endurance. It can apply equally to a great truth and to a great lie..." 3. The step from sheer size to social awareness was made by Siegfried Giedion: "Monumentality derives from the eternal need of the people to own symbols which reveal their inner life, their actions and their social conceptions." The presence of social aspects of architecture, and hence monumentality4, was abundant in the modernist movement, resulting in the CIAM Athens Charter of 1933. This document set down the functional requirements of new cities. Leaving behind the terrors of both World Wars, the modernist movement has started persuasive attempts to monumentalize community life. The paramount example is the erection of Brasília in Brazil by Lúcio Costa and Oscar Niemeyer. As the entire city is thrown up in about three years time, it has had every opportunity to be raised to the intention of the architects. Due to the completeness of the commission and the emptiness of the location, this city provides a unique case-study: a full-fetched, uncluttered urban design rendered and designated to its utmost capacities. Here lies the ideal research project for a search into the monumental.

It is in the monumental that a society is reflected, and vice-versa in the reflection that society provides for the monument. Yet, the modernistic semblance of Brasília does not immediately call to mind the memorial powers of for example a war monument or a Roman obelisk. Somehow, there is a mismatch between the symbolic representation of the memorial which we intuitively connect to the monument, and the idealized advances of the rudimentary geometry of Costa’s master plan and Niemeyer’s ministries. The latter does not immediately give way to explanatory stories about the social or cultural; the iconoclastic language of modernism simply does not allow for that. Post-modern escapades of recent architecture have passed by this question and returned to a more iconographical perception of architecture, but the modern monument left its not yet fulfilled incentive. The social motive of the modernist architects, and their capacity to explain architecture by means of social constructs, contrast sharply with this incentive, leaving us an intriguing question to the way in which this story is told. The architecture is a signifier, but what does it signify5? More practically, what instruments did Costa and Niemeyer deploy to tell their architecture, and how did they employ them? A special case is made here for the monument in this discussion, for I believe that monumentality exerts a crucial role in the conflict between architecture as the signifier and cultural exposition as the signified.

Definitions

To pinpoint the importance of the notion of the monument in the intimate relation between story and storyteller, we first have to arrive at a meaningful definition of the monument. After all, what is it? The word stems from the Latin monēre, to remember, remind, and the suffix –ment, indicating a result or an action6. Etymologically it thus means that which sets the act to remember. It signifies the memory, by means of inscription, the symbolic or the iconic. It provides me with an image, reminding me of something else. Yet, that is not all. The mere image would not be monumental (at best it would be a rhetoric shell), because it does not yet proclaim the very suffixal act of the monu-ment. A monu-ment in this sense explicitly designates a spatial context: we have to be close to it in order to be aptly instigated to the act of commemoration. A place needs to be provided for the act. An image needs to be provided for the memory. The monument, it seems to me, makes a strong appeal to both.

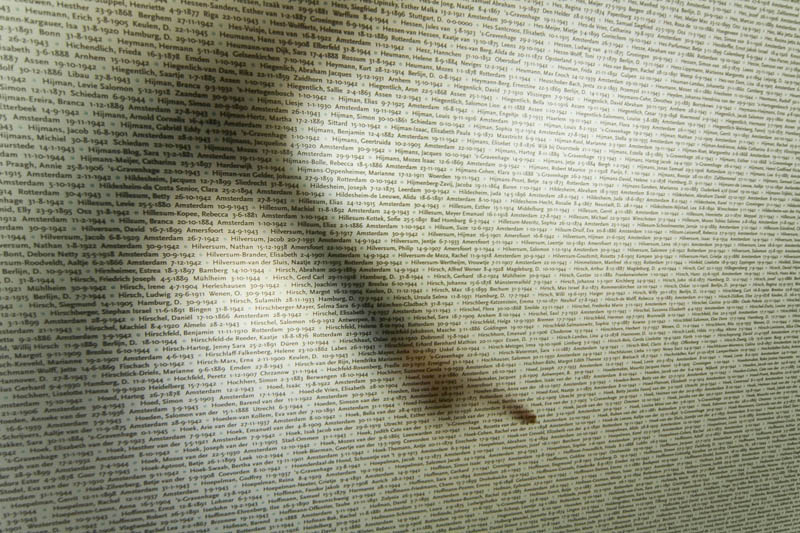

An inscribed wall with a memory to names from Auschwitz

Either of them alone would not suffice to describe what comes to mind with the sense of the monumental. The act of signifying mere memory belongs not intrinsically to the object of thought, but to the thinker: I am reminded of something. It seems paradoxical that this reminding occurs in a passive sense, but the paradox resolves when we take into account the reflexivity of the moment of remembrance. As soon as I see an object, I myself connect a past event to the here and now. Thus, the memory strikes back at me, it reflects, it is reflexive. Any object has the capability of retrieving these specific memories from someone’s mind, yet these memories are not transmissible through the mere object. Take for example an inscribed wall. Such a wall, largely a blind one to ensure that the beholder is not distracted from its message, portrays a list of names, some known, others forgotten. Its size tries to impose its importance upon us, though whether this call for attention is successful depends on our readiness to endure it and our willingness to open our mind toward it. Then, we are drawn to the inscriptions themselves. They seem blank, faint and dense. They are unfamiliar and endless. We pass by them, step after step, but our eyes fail to catch any peculiarity. The magic of the first moment (when the wall still succeeded to impress us) subsides. The names: we do not know them; we cannot even read those smaller ones on the top, until someone (presumable a guide of some kind) enlightens us: these are the names of all 110.000 Dutch deportees – most of them jews – killed by the Nazi’s and ever refrained from a grave7. Now, a shiver or a respectful awe overtakes us. We are impressed, fall silent. Only now we remember.

The example indicates that we need a memory to simply remember something, but a place to commemorate it. The act of remembrance can be performed anywhere, anytime, but the monument sets this act to a specific place, and a specific time. This is the second characteristic described above: the suffix to remembrance, the remember ment. On its own, the settling of the act does not suffice to describe what we sense to be monumental. The place cannot do without the memory. Such a hollowed out sphere, acclaiming a blankness which leads nowhere and inspires to nothing, might presumably be called a centre of meditation. Again, similar to the memory with no place, the place without memory triggers a reflexive moment, yet this time an unspecific one. Here, I cannot let myself be guided by the outside, and have to retain solely in my intimate self. In fact, the same nameless wall of the description above, ascribed with so many unknown names, can portray this feeling as long as its purpose or intent is unclear.

The monumental and the social

As a monument commits to its two characteristics of memory and place to commemorate, it readily becomes architectural. For, as I have tried to show above, the monument is explicitly tied to its spatial situation, and only from this occurrence the commemorative is able to arise. Its spatiality links monumentality to architecture, but the tie also works the other way around: monumental architecture relates to a cultural context outside of itself, and as soon as architecture becomes monumental, it operates in complete subservience to some externally defined ideal8. But this is only half of the story. For architecture to become monumental, or the monument to become architectural, the architecture has not only to reflect upon its cultural context, but also upon itself. To put it succinctly: building which fails to reflect upon itself is no longer architectural. For what claim to the architectural can such activity of mere building make? In the monumental, taking into account its complete subservience to a cultural reflection, it can make none. The architecture becomes merely a mirror. When Adolf Loos wrote "only a very small part of architecture belongs to art: the tomb and the monument"9, he reminded us of precisely this point: architecture is mere practical building as long as it refrains from self-reflection, and as soon as it yields to self-reflection, it becomes monumental. The three (architecture, monument and reflexivity) become bound up in a coherent and self-induced way. This is by no means a methodological claim, but rather an experiential one: As soon as someone claims this or that to be architecture, he implicitly attaches the notions of monument and reflexivity, and vice-versa.

In this view we need the architectural in order to create monuments and hence in the monumental the architectural cannot reflect solely on what is outside of itself, but must address its own "true nature, [..] proper means, and [..] legitimacy of existence"10. The unfailing link between monumentality and architecture makes sure that the latter has a place in society (upon which it reflects) and consequently obtains a role in it, albeit solely for reflection upon itself. The social role of architecture, without the remark on self-reflexivity equals the modernist aspirations of monumentality. As soon as we allow the capacity of architecture to be only respondent to itself, and nothing beyond itself, we face either Exodus or Bigness, to speak with Koolhaas: In the first, a strip inhabited by "Voluntary Prisoners", one discerns from the outside "serene monuments", while "the life inside produces a continuous state of ornamental frenzy and decorative delirium, an overdose of symbols [..] This strip is like a runway, a landing strip for new monuments."11 The "inside" of Koolhaas’ Exodus is disconnected from the city, stands on its own. What appears as monument from the outside, is in fact not, for it cannot symbolize or signalize something other than itself. In Bigness, Koolhaas administers the same idea of lost relationships. Interiors and exteriors no longer communicate a story of "honesty", nor is the impact of architecture dependent on its quality. What rests, apart from an undeniable and self-evident object, is Bigness. "The best reason to broach Bigness is the one given by climbers of Mount Everest: "because it is there"."12 We come to the point that a relationship between society and architecture is undeterminable, but at the same time inescapable.

Not bothered with these negative qualifications and fatalistic ideas, modernist architects set out to establish the link between the social and architectural, by means of the latter’s reflection upon society. This is essentially monumental, as I have tried to show, but the focus is no longer on size or overwhelming appearance. CIAM took upon itself to advance these ideas, but they were not the first. In 1914, Antonio Sant’Elia wrote in his Manifesto of Futurist Architecture "We have lost our predilection for the monumental, the heavy, the static, and we have enriched our sensibility with a taste for the light, the practical, the ephemeral and the swift."13 Thus the technical becomes a new means to express the ways of society through architecture. Le Corbusier alluded to the same when he expressed his credo: "A city made for speed is made for success."14

The role of architecture in society described through the monumental gives a useful entry into a description of architecture in a public sphere; for it is only there that it can perform its societal part. This thought indicates the main line of my further investigation into Brasília, a city spoiled with monumentality.

Brasília

The city of Brasília, the ever-new capital to Brazil, was created out of nothing in three years time. "Nothing" is quite to the point here: the vast emptiness of the undulating plane on which the city lies is nowadays characterized by a population density of about 4 persons per square kilometre15; back in the fifties, when the city was built, the density approximated only 1 person per square kilometre. Oscar Niemeyer noted that "it was a huge and dismal patch of wilderness in the remote central interior plane"16. Establishing this city here, away from economical or political powers, was an act of shear symbolism: the capital now occupies literally the centre of the country, empty though it is. Projected as a circle, Brasília’s centrality to the rest of the country signifies the equality that roams through the city, and it is precisely this to what Luis Costa’s plan acclaims its social qualities (at least as it was perceived at the time of the commission).

Brasília as geometric centroid of Brazil. Reproduced from a diagram in James Holston, The Modernist City; an anthropological Critique of Brasília, university of chicago press, chicago, 1989, p. 19

The theme of equality is paramount in the structure of the city, but it is not alone. On another level, maybe even primary to the former, the city is hierarchical. The "wings" of superquadras are crucially tied together at the centre. Thus, between the gulfs of equality hierarchy is established. This is a recurring theme in the city, as can be seen in the plans for the superquadras: All buildings constituting a quadra are equal, and so is their distribution. Yet, the quadras are connected by intermediary squares and lanes, which clearly provide for a restrictive declination of privacy: the farther away from ones front door, the more public life gets. This, on first insight, organizes the equality of the city in a hierarchical way.

But let us return to the centre. This no doubt is the most intriguing spot of the city. Yet, the very umbilicus17 of the city is again a vast, empty terrain. On the scale of the city, Brasília repeats what happened earlier to Brasil: an evident loss of centre due to a circular displacement. This centre, however, is not filled up, and the displacement is now not circular, but almost linear and directed away from the point of gravity. Here, we see Luis Costa’s work to the full extent: the capital, central city, is denied its own proper centre. We might recognize a strange chiastic topic here. On the one hand, the equality of the social conditions and living premises is established through an hierarchical order. On the other hand, the hierarchical control structures of the city are an expression of the social equality of the city and the country.

This second remarks becomes more meaningful if one investigates the role of these control structures. The Square of Three Powers, at the one end of the central void and at the geographical centre of the city, is itself again laid out as a equilateral triangle. Once again, the centre is empty. Surrounding this middle are the three democratic powers of the trias politicas: the legislative, administrative and judicial power. Together, they signify the constitutional powers of democracy. Here again one finds hierarchical power centralized around, but not in the middle of a centre. Yet this is not all. Of the three, the congressional buildings dominate the square and the urban skyline, introducing another level of hierarchy. And again this hierarchy is accompanied by a reminder to equality, for it is through the democratic power of the congress that the equality of man should be safeguarded.

This reading of the cityscape of Brasília entails a capricious interplay between control and socialist ideals. Whether this reading is always accurate, is painfully shown by the political troubles happening right after the inauguration of the city in 1960. In total disregard of the architectural expression of equality through the National Congress, a military coup held tight to the power until the late eighties. As such, the interplay might better be described as an architectural manner than an architectural link to society.

We have seen how the relationship between society and urbanism has played an important role in the layout of the city, but also how little of this relationship can be felt by society if a sudden change is instigated. The speed with which architecture can adept itself to new situations might naively be questioned, but that is not the point here. The relationship between society and architecture is dependent on interpretation, first of the designer, second of the beholder. Arguably, Costa’s and Niemeyer’s intentions were alright, and as followers of communist theories18 both did well to exemplify through their eyes the major benefits of such a conviction. Yet, we cannot conclude from this that their building is monumental, for even though at some point it resembled society, on its urban scale it could not clearly and openly instigate a place where society could reflect upon that resemblance.

The Monumental City

From the outset, the city of Brasília was not only meant to be a socialist structure. The president of Brazil, Juscelino Kubitschek, had a strong mind for a new capital, and his intentions were growing. As Niemeyer remarks: "He [Juscelino Kubitschek] came to my house at Canoas and eagerly told me of his plans as we drove back to the city together: "I am going to build a new capital for this country and I want you to help me." He still had that same enthusiasm of twenty years before. "Oscar, this time we are going to build the capital of Brazil. A modern capital, the most beautiful capital in the world!""19 A bit further in his memoirs, Niemeyer betrays his own enthusiasm as well: "JK's vision - and mine, too - was not one of a backward provincial city, but of a modern and up-to-date city, one that would represent the importance of our country."20 Costa’s plans might have revealed some restrained socialistic sincerity; these utterances mark a wild excitement for a grand scheme, some proliferation of previous gestures of monumentality.

National Congress at the end of the monumental axis. The blocks at both ends represent several Brazilian ministries.

Here, we stumble upon a completely different aspect of Brasília, namely, the strength of monumentality sought after by idealists of the nineteenth century, or the power of innovation and progression expressed by the Futurists and, subsequently, Le Corbusier. Strength expressed as technique, and technique as expression of social equality: the roots have not changed so much. But the technological progress does not only come forth from the will to social justice. As J.R. Curtis says it, Brasília embodies the "old dream to expand towards the heart of the country"21. The city exemplifies the will to be modern and does so in a technological way. The infrastructural system was designed to link the three key-functions of life as they were written down by CIAM: living, working and recreation22. It is in concord with the earlier-cited maxim of Le Corbusier: A city made for speed is made for success23. It is in between these infrastructural spaces that room is explicitly left for the monumental. One might say that the monumental is, in this sense, functionalized and reduced to be only one of the many dedicated areas of the city. This view is repeated by José Luis Sert, Fernand Léger and Sigfried Giedion as the eighth of their Nine Points on Monumentality:

"8. Sites for monuments must be planned. This will be possible once replanning is undertaken on a large scale which will create vast open spaces in the now decaying areas of our cities. In these open spaces, monumental architecture will find its appropriate setting which now does not exist. Monumental buildings will then be able to stand in space."24

We see now how the ambition of the Brazilian president corresponds with the ideas of the modernist movement: the issue of representability is treated in its own, specific place, thus making sure that it is treated with adequate attention. Whether it is necessary to do so, or whether this treatment leads to the kind of representation aspired to, is beyond the questioning: the scheme for the city plan makes clear that the issue is treated, not how.

I started out this essay with a definition of the monument as a place to remember. The scheme of the city clearly offers such a place. But to be monumental, and to have a place in society, this place should trigger a memory. It is in this respect that the architecture of Oscar Niemeyer abandons the path of the modernistic, technological approach. His architecture of power, the two standing towers of the National Congress, his two sculptural hemispheres beside it, the Cathedral down the avenue or the JK Memorial – all of his architecture shares an ungraspable smoothness which lingers easily in the mind, but is hard to characterize. Often the National Congress is compared to Le Corbusier’s scheme for the United Nations Head Quarters in New York and Hannes Meyer's design for the League of Nations Building in Geneva, because it closely resembles them in form and function25. But if we want to understand why this building is so persistent in our memory, these comparisons provide no answer. What is remembered from these buildings is not the social institutions that they signify, not even when they fail to do so, nor their marked spot in the urban fabric of the city. Not even the monumental axis itself is remembered because it divides the city in two perfect halves – in fact, the growth rate of the suburbs rapidly abolished this fact. Rather, when I see these buildings, the monument for the Satellite Cities of Mexico created by Luis Barragán springs to my mind. A structure erected without perceivable function, this building, as well as Niemeyer’s, give way to a remarkable recognisability together with an ease and allowance to personal memory. Here, a space is created where one can simply be in awe, without being troubled by social problems, expressions of power or references alluding to international organizations.

This kind of expression, touched upon by both Barragán and Niemeyer, might be called rhetoric, for it is persuasive: it cannot easily be ignored. Yet, neither of the two link this gesture of persuasion to a definite meaning, nor make they any pretention to do so. All of the ingredients for a truly social or truly technological reading shimmer in the background, used out of convention, conviction or practicality. In this way, Niemeyer came very close to what I have earlier called monumentality: to settle the act to remember. He provides a place, and a memory, both far from neutral, but at the same time far from determinable. It is only through the words of Niemeyer himself that these considerations could best be conveyed:

"I do not know why I have always designed large public buildings. But, because these buildings do not always serve the functions of social justice, I try to make them beautiful and spectacular so that the poor can stop to look at them, and be touched and enthused. As an architect, that is all I can do."26