The essential question for architecture in a western society focuses on the relation between the city and architecture. Architecture in the city has as a primary objective to accommodate public life 1. Public life in a contemporary city means primarily to live together with people we do not know 2. In this essay, I question the conditional relationship between city and public life. The question I try to answer is: what context does the city offer for public life? Architecture, as the discourse which develops the built environment, makes the city. If, therefore, I ask about the urban context, I do this only to find out how, eventually, architecture is involved in the conditions of the ‘urban’ or perhaps, how architecture is conditioned by these considerations.

The vicious circle of modern architecture

How have we come to consider the city as a condition for architecture? Anthony Vidler identified in his 1977 essay The Third Typology two historical foundations for architecture. The first typology, as he labelled it, establishes itself on an idea of rationality. Its historical roots lie in the enlightenment call for justification, and an honest belief in the possibility to solve architectural problems on the basis of a rational chain of argument. Its idealistic reference, obviously, is nature, as in nature redundancy and inefficiency are evolutionarily filtered out. The second typology on a similar basis foresees a conditional role for technology, in order to create social welfare and abandon social inequality 3.

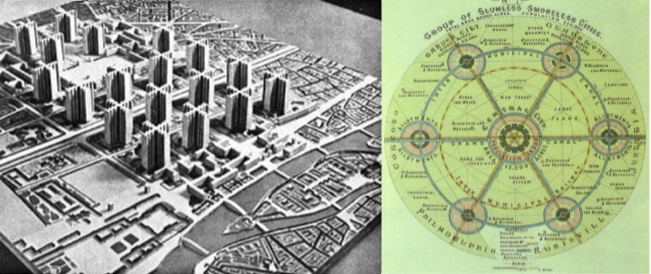

Radiant City by Le Corbusier, vs. Garden Cities of Tomorrow by Ebenezer Howard

Vidler recognizes, however, that neither of these conditions can acknowledge the complexities of urban life and architectural situations in an urban context. Modernity, the transitory drive to progression, has rendered the natural and technological insignificant as typological basis. In fact, as neither can answer to the complexities, it becomes clear that both typologies cannot sufficiently ground architectural form. Another referential condition for architecture arises, Vidler argues: the city itself. But as the city itself is made of architecture4, it becomes self-referential. The form of architecture derives directly from its close environment, which is no longer a reference to some ideal outside of that environment, whether it is natural or technological. The city reveals itself as the sole context for urban architecture.

When the urban context of architecture was first argued as an essential condition, a cultural aspect formed the basis of research into the architectural form. Ernesto Rogers called for a consideration of the pre-existing surrounding, and wanted architecture to start a dialogue with this environment 5. Aldo Rossi continued this call for an understanding of the city in terms of primary urban facts which constitute our collective memory of the city – it is by means of the matter from which the urban facts are built that we can read and experience the city, but the memory itself transcends the mere material aspects 6. Rossi finds that their memorial value is attached to their appearance, or outer form 7. The urban context, then, deals with the collective memory or consciousness of these remembered forms rather than with the direct built surrounding, and through architectural form this collective memory can be maintained.

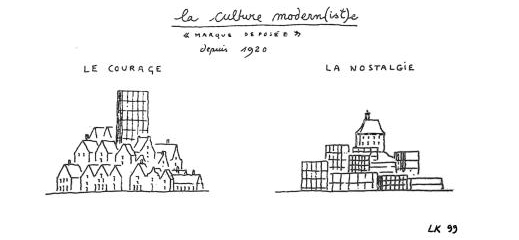

Despite Rossi’s call for a revaluation of urban cohesion in architectural projects, modern architecture has detached itself from the collective memory. Both his and Rogers’ approach have been superseded by globalist aspects: we live in a society that regards the visual, rather than the urban facts, as the most pragmatic and easily accessible feature of a (cultural) context. The promotion of the visual as communicator of cultural values signifies a loss of a true architectural memory, in Rossi’s sense. Guy Debord summarizes the growing influence of the visual and the rupture it implies in his understanding of the spectacle:

“The spectacle, like modern society itself, is at once united and divided. The unity of each is based on violent divisions. But when this contradiction emerges in the spectacle, it is itself contradicted by a reversal of its meaning: the division it presents is unitary, while the unity it presents is divided.” 8

In this specific context of the city as architectural condition, we find problems of attachment related to the visual propagation of modern society. While the structure of modern cities converges to an image of itself, reflexively acknowledging the architectural context as the sole condition for its architecture, its inhabitants are at a loss. They appear to be detached from the architecture of the city surrounding them, as the architecture itself appears detached from the specific surrounding. Juhani Pallasmaa acknowledges this loss of cohesion in modern public spaces: “They seem .. to project a sense of isolation, separateness and solitude” 9. The stilled image of the city itself has, in its self-referential third typology, come full circle to its own basis, thus excluding external factors such as its inhabitants. The vicious circle of modern architecture excludes the people from its domain.

Projections of the city, by Leon Krier

If architecture is so detached from modern society and the cultural exchanges of its occupants, how then should we understand a modern society in an architectural context? What, in other words, is the value for such a context for the appreciation of public life? If not formally, how can we read the city as a viable social context 10?

The context for public life: an urban environment

The loss of cohesion between the city and its inhabitants is not only a critique on architecture, but part of a broader context. As Guy Debord already made clear in his critique on society, the disability of people to see themselves other than through an image, detaches them from their environment, but also from each other. Debord’s society centres on the notion of the commodity, the capitalistic ideal of individual freedom: the ability to consume removes any constraint on the scope of our material lives. The valuation of the commodity, however, implies a loss of valuation for immaterial aspects of life. The image, or spectacle, is the utmost demonstration of this loss. We perceive the material objects through nothing but its visual features. Debord could not have imagined the far-fetching developments of his spectacular society in a world as ours – tied up to the virtual second world of the internet, our society has extended its real component towards a disconnected virtual addition which takes over more and more roles of traditional public life.

Debord’s warning for the erosion of public life echoes in the architectural developments discussed above, but their effect is consequential rather than causal. The condition of modern, public life has other disengaging propensities as well. To live in an urban environment means essentially to live amongst strangers 11. In a city, we get in touch with people, to whom we are not familiar, people with other, and maybe different, habits, people with whom we are not socially interacting. This situation, the urban condition, is both a relief and a threat. A relief, because in a city we attract no attention, we can disappear in the crowd and we can retreat into anonymity, as if we were momentarily part of a continuous routine, a mechanical urban rhythm in which an individual draws no attention 12. Precisely on the common ground of public life we do not have to open ourselves completely, as we can behave in concordance with established norms.

Simultaneously, the urban condition holds a threat. In the mechanics of a city, the ongoing rhythm of day and night, each individual falls away against a bleak, never absent background. The urban condition is always there. We cannot stand out of the crowd, nor can we withdraw from it. We are, however, continuously reminded of it: opinions, reactions and unexpected events confront us ceaselessly. In a modern city, the confrontation of conflicting expectations is the condition on which public comes together 13. We thus experience a continuous rift between those with whom we share a perhaps unconscious norm, and those with whom we share nothing; nevertheless, we are always unaware to which group an accidental passer-by belongs.

Urban planning in Rotterdam

The condition of the city itself, then, always tends to push us away from it. In a city, we behave as if we do not belong there, holding off unnecessary contact 14. The remarkable few who dare engage in social communications are met with surprise and mistrust 15. In public life, in other words, we do not live together, but separate from each other, avoiding potential conflict. Virtual life and consumerism have enhanced the ideal of valuating individuality and evading public accountability. We cannot regard the city as an entity any longer, in this respect.

Many theorists of architecture have, after the rejection of technologically driven modernism or nature-based socialism, administered the incredibility of a unified city. First, Michel Foucault recognizes the twentieth century as the juxtaposition of spaces, multiplied and isolated from each other. These other spaces, profane and deviant from a norm, he coins heterotopies 16. Others, such as the Smithsons, acknowledge that “we don’t experience the city as a continuous thing anymore, rather as a series of events” 17. The Japanese architect Kisho Kurukawa even went as far as to declare the capsule as the model for future architecture 18. Lieven De Cauter, who brought together all these attempts to breach the unitary city, takes over the idea of the capsule as the most prominent way of understanding the contemporary city. He finds that technological and infrastructural progress contributes to the so-called capsularization of society: it infers less exchange through personalized and individualized possibilities of transport. The German slogan “a car for everybody” in this sense means a disruption of social life. Transcendental capitalism, recognized by De Cauter as the only and all-encompassing political reality 19, is similarly an instigator for capsularization: the economic process of consumerism converges to an insurmountable social duality between centre and periphery, rich and poor, participants and dropouts. A third characteristic of capsularization, both cause and effect, De Cauter termes hyperindividualism – the inescapable refuge into one’s own private world; a flee from the accountability that belongs to a shared society 20. Hyperindividualism is a process analogous to the relief of losing oneself in a crowd.

In the description of the urban environment as negative, capsulated, transitory, mono-sensual, and without cultural connection, in the erosion of public life, we find a common tendency towards a believed crisis of identity, or a failure in the description of society “as it is”. The failure manifests itself in an uncanny, perhaps even fearful feeling among members of society: problems of identification, for instance, control the contemporary Dutch political debate. Abundant in these discussions is the ability to name perceived problems, whether real of not, and subsequently the rhetorical exposition of vigour and control 21. The solution to the problem of description, however, lies not in the attempts to single out one perceived identity above others. We might therefore, when discussing issues of identity, refer to Theodor Adorno’s description of the nonidentical:

“Reality is nonidentical: reality is not simply what it is, it does not entirely coincide with itself, but continually refers to something else, to something more than itself: “That which is, is more than it is. This ‘more’ is not something that is annexed to it, but is immanent in it, because it consists of what has been repressed. In that sense, the nonidentical would be the thing’s own identity as opposed to the identifications imposed in it.” ” 22

A description of the reality of the city as a context for an architectural intervention, then, can only be sketched through the nonidentical accumulation of interpretations of this reality. What is subsequently found in such a plural interpretation is a gathering of conceptions that might invoke some understanding of the ‘more’ which is immanent in the reality the interpretation depicts. In other words: when accumulating interpretations of reality, we approach reality itself. Multilayered, juxtaposed, stacked on top of each other: the search for identity leads to an accumulation of information. The only way to describe the underlying sense of a coherent entity, of id-entity, is through this multilayered complexity. The ‘more’, or the transcending value of the material world, can only be described by means of circumscription, by stacking layers of information on top of each other. Such an attempt has been made by Italo Calvino in his 1972 novel Le città invisibili, in which he has Marco Polo describe 55 cities. These descriptions turn out to be imaginary, all reflecting Polo’s home town, Venice. Thus, by describing invisible dream-cities, Calvino manages to circumscribe a real city 23.

In circumscription we might find a viable instrument for research into the complexities of the contemporary city, both as an exponent of architecture and as a gathering of public life. A valid architectural answer to the complexity of the city derived from circumscription lies with the acknowledgement of its multiplicity, the acceptance of the loss of cohesion. What physical implications can be drawn from that understanding?

An answer might be found in the agenda Bernardo Secchi has proposed for architectural research:

“Among the origins of the progressive, but still incomplete, partialisation of society there are, at least in my opinion, two phenomena: the first has to do with the sphere of consumption behaviour in a mature society, while the second is related to the sphere of the norms which seek to regulate the interaction among the society’s various components.” 24.

Secchi understands the problem of a multi-layered and partialised society as a problem of accommodation. Different forms of appropriation of space, according to Secchi, can only develop when enough time is given for practices to unfold there. Implicit in his thought is Rossi’s argumentation that time constitutes memory, whether collective or individual, which eventually establishes identifiable values 25. A solution to the problem of modern isolation and solitude might then simply lie in the re-establishment of these historical and recollective ties throughout a city.

The loss of cohesion in casu: Rotterdam

The city centre of Rotterdam is a remarkable case in the discussion of modern public life, as the entire centre is rebuilt in terms of a response to the modern condition. It can be regarded, in other words, as the separate and solitudinal projects Pallasmaa refers to 26. In addition, its public is as mixed and therefore as unfamiliar to anyone as might be expected of a lively harbour town. Since the horrors of the World War 2 destructions, Rotterdam has established itself as the city of progress. Its harbour has grown to become the second largest containerport of the world, its centre is home to many multinational headquarters. City planning was based on functionalist ideas of separation and sanitation. Marginal or liminal spaces were deliberately removed from the urban planning. Rotterdam is the material representation of economical progress and the corresponding increased prosperity. In fact, with city slogans as “Rotterdam dares” and “Here pounds the new heart of Rotterdam” 27, the city government explicitly refers to its core business of the development of progress. Simultaneously, Rotterdam scores low rates on national safety figures, the government regards its city centre as dysfunctional and its inhabitants are dissatisfied with local policy to settle social issues. It thus answers in full respect to both the argument of capsularization and the understanding of modern-day capitalism as put forward by its critics.

The problems of Rotterdam might be summarized as a lack of cohesion: between buildings and people, between different publics, between different social classes. The prospect of Bernardo Secchi that enough time might allow for better appropriation of urban spaces could until recently not materialize in Rotterdam. Its policies were directed at constant renewal of its urban structure, thus denying the possibility for memory to establish, or for Secchi’s appropriation to take place.

We thus recognize in Rotterdam a disconnection of memory and place. However abruptly this disruption has been caused by a historical event, the tendency has prolonged because of the characterization of Rotterdam as a new city; new proposals to the urban structure have, since the reconstruction plan, been regarded as replacements rather than additions. If we want the connection between place and memory to be repaired, or new connections to be made, we should allow for that by giving time. That asks for a different attitude towards the existing urban structure: it should not be considered as fallen-behind examples of progress, which block the ongoing pursuit for new progression, but as valuable contributions to what once was considered modern.

We should allow modernity, perhaps, to get historical.